Our Last, Real Estate

By Robert Locke, Pseud. Clayton Bess

All rights reserved. This manuscript or any portion thereof may not be used or copied in any form by any person or corporation without written consent of the author.

© Robert Locke June 11, 2009

Family Silver

To Cheryl from Her Uncle Bob

"Uncle, that's the next story you've got to write."

It was a story I didn't want to write, but I put that into the back of my head; my niece Cheryl thought it was important for me to write it. Cheryl, my oldest brother Clay’s daughter, was on the verge of foreclosure on her treasured riverfront property in the California foothills, and for some reason I can’t remember I had confessed to her this story of mine.

"Uncle, that's the next story you've got to write. All those years you were taking care of all those sick and dying people, and they never knew?”

“Your Uncle Richard knew. I think we got it just about the same time."

"Grandpa never knew? Grandma never knew?”

“She couldn’t have survived it. Your Uncle Richard’s death almost killed her.”

“Uncle, you’ve got to write that."

So a few weeks ago, I got out of bed in the middle of the night, the story cycling in my head, compelling me—in the same way that my first book Story for a Black Night had compelled me—to get up and write, to get the story down, the words out and organized, the ironies plain.

By the time I finally got to this writing, Cheryl had in fact been foreclosed upon and evicted suddenly with only the clothes on her back. Her real estate business had gone bust during the bursting of the “real estate bubble” throughout California and the nation. Cheryl had hung on for months by her fingernails, clawing together money to feed her animals—always her animals first—but losing, in terrible increments, her all: her little retail shop of used clothes, her pick-up which was core to her livelihood in rural real estate, now her house and finally her animals, the four dogs and two cats that she had rescued through the years from the riverbank where they had been dumped by other hapless or perhaps simply uncaring owners. In the end, evicted by the sheriff himself, with no further resources and now homeless and on foot, she could find a home for only one of the dogs, a young and handsome puppy. The others, lame and old and unwanted, she felt she could not abandon on the riverbank as before, to die of starvation, finally the coyote. She had to put them down.

I fear she used a gun borrowed from a neighbor, but I can’t bear to know. Those trusting eyes—no, I can’t allow that picture into my head. But with her animals depending upon her for food, for comfort, for a home, and with no home, no money, and tools borrowed from a neighbor, tools, tools, I picture—yet cannot picture, will not picture—she must have finished the job in the countryside, burying them, marking the graves somehow, but I can’t bring myself to ask her about any part of that.

I can’t begin, can’t even begin to imagine Cheryl’s distress at these losses.

But the one thing I can do for Cheryl is what she asked me, commanded me to do: write my story. And now I have done that. Now, however, my story intertwines with her story in new ways, and a new story demands to be written. New, more complex ironies swarm through my brain these sleepless nights begging me, commanding me to get up, to get these stories down, and together, and to try, at least, to get these new ironies straight—these fresh ironies twisting around and among those three plain words “real” and “estate” and “bubble” conjoined in so dreadful a commonplace in our news today—and to sort through all that this means to Cheryl and to our family. To our family, yes, and to how many other families, searching for silver in so black a night?

Another Garden

By Robert Locke, Pseud. Clayton Bess

© March 21, 2009

It was one of those golden, gentle days in the fall of the year. I was digging in the garden, planting bulbs, the autumn leaves blazing all around me. And there was so much to think about. The ever present thought, always nagging now around the periphery of my jagged mind, was whether it wasn’t simply foolish to be planting bulbs again this fall when it was so doubtful that I would still be alive in the spring to see the blooms.

At the beginning of that year, 1983, I had gone to see a doctor. I had a lump in the back of my neck that was not going away, a lump I feared might be cancer. “No,” the doctor told me. “You don’t have cancer. What you have is a new disease that is attacking gay men in New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles.”

I was living in Los Angeles; I was about to return to San Francisco; I had always wanted to see New York. Now I was to understand that this was doubtful.

“These men present with swollen lymph nodes in their neck, like yours. Within six months, they’re dead. We don’t know what it is yet.”

Brutal. I never saw that doctor again, but I have seen many since then.

I remember stumbling out of that office onto one of those broad boulevards in Los Angeles, blinded by this news and the stark, white, southern California winter daylight. It was the very beginning of the epidemic that was to be called AIDS, soon to become pandemic. HIV—the virus that caused the disease—would not be discovered and named until more than two years later. The total known victims were still in the triple digits, with Larry Kramer’s landmark article of outrage in the March 7, 1983, issue of the New York Native still two months away: “1112, and Counting.”

Until that day I had been upon the brink of something wonderful and life-changing. After ten years of searching for a publisher for Story for a Black Night I had finally succeeded beyond even my own wildest dreams: a big Boston publisher, Houghton Mifflin Company, had brought out the book in the fall of 1982. It was greeted by starred reviews and even some awards and it looked, after all, as if it would have a good, long life. Houghton had even accepted my second book now, and this “now” was getting continually better. Now I even had a contract in my pocket to have my first play The Dolly produced that very spring as a Play-in-Progress by a big theater company in San Francisco. Now my career was finally about to unfold on both coasts at once, both as Robert Locke, Playwright, and as Clayton Bess, Author of books for young people and children.

Now, however, on that January day—the first Monday of the New Year—on that boulevard in that bright light where I stood trying to focus, I began to understand that what was now unfolding was not a new career after all. The brink that I was upon, I now saw suddenly but not yet very clearly, was the brink of death. I had a killing disease that no one in the world even had a name for yet.

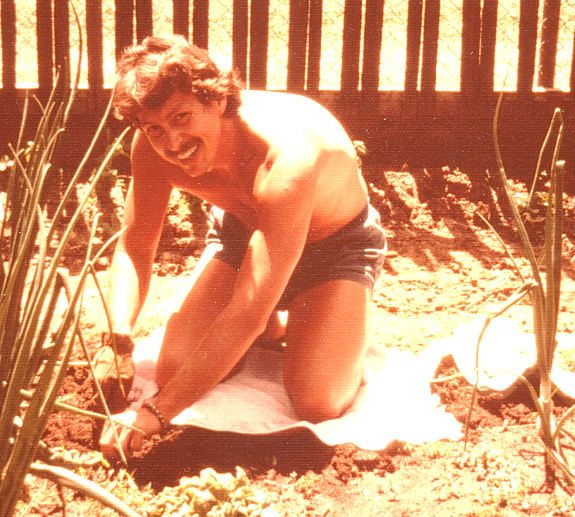

So, those nine months later, in the golden autumn light and warmth as I knelt on the ground and planted those flower bulbs—daffodils, tulips, crocus, narcissus, I remember—I was contemplating all this, still trying to make sense of it. I had outlived the six months the doctor had predicted, but what now? The Play-in-Progress production by the American Conservatory Theater had been so powerful, starring such huge and bright talents as the up and coming Annette Bening, that it was now to be produced on ACT’s main stage. The Dolly would be performed for an entire month the next June in San Francisco’s magnificent Geary Theater in front of an audience of twelve hundred people each night.

But would I be among them? It was only October. June was another eight months away. And at that very moment, that now, as though I was taking a candid snapshot of myself, I had a revelation. I remember that I even sat back suddenly on my heels, took a deep breath, and looked all about me at the fiery leaves, the final ironic words of Candide popping deliciously into my head: “…il faut cultiver notre jardin.”

How perfect. How perfectly wise of Voltaire to end his wickedly funny novel of human miseries so neatly, with Candide taking up Dr. Pangloss’s ever-too-wide brush of optimism to repaint our “best of all possible worlds” so simply: “…we must dig in our garden.”

Or really, I thought to myself, a better translation would be “…we must tend our garden.” Or better perhaps, “…we must plant our garden.” Or no, perhaps cleaner, perhaps simpler, perhaps more faithfully, “…we must cultivate our garden.”

But I did really like best my first idea, and so I returned to my digging, and the thought made me smile. In fact, at age 39 I still felt like a kid, and that felt good, digging in that warm, clean soil in that golden autumn sunlight, having what was essentially an epiphany: now, very simply, I must dig in my garden.

I must plant bulbs in the fall whether or not I live to see the blooms in the spring. I must keep writing, hoping to complete the next novel, the next play, hoping to live to see them published and produced. I must live every day both as if it were the last of my life or the first of the rest of my life.

NOT THE END

Picture please (here are photos, but picture in your mind first please) Cheryl and her Uncle Bob digging side by side in a small bed of flowers--a splendid carpet of reds and pinks and purples on a hill between two bays, mountains in the distance--before three gravestones of rose granite marking our last, real estate.

|

RICHARD HOLT LOCKE June 11, 1941-Sept. 25, 1996 Beloved son of Bess and Clay At rest with God |

|

Echo of centuries: Remember… |

|

TOGETHER AGAIN |

|

|

CLAYTON EUGENE LOCKE Feb. 28, 1914-May 10, 2000 SUCH A SWEET GUY “Today is today; Yesterday is yesterday.” |

BESSIE JEWEL HOLT LOCKE Sept. 13, 1913-June 26, 2007 SO LOVING “You can write it in your daybook; we are comfortable now.” |

|

GOD BLESSED THEM WITH LOVE, HAPPINESS AND A WONDERFUL FAMILY. |

|

|

…Remember, you’re not here alone. If voices are muted, words are engraved in stone.… |

|

ROBERT HOWARD LOCKE Dec. 30, 1944- Pseud. Clayton Bess “Love is a word with a lot of heft.” |

|

…Oh, remember, you’re not here alone. |

THE END

Copyright © June 11, 2009, rev. July 8, 2009, Robert Locke

All Rights Reserved